Forty-five years ago this month, the Supreme Court ruled on a UFCW case and gave workers a big victory. That case established “Weingarten rights,” which allow workers to have witnesses sit in on meetings or communications during which managers ask about matters that could lead to the discipline of those workers.

Forty-five years ago this month, the Supreme Court ruled on a UFCW case and gave workers a big victory. That case established “Weingarten rights,” which allow workers to have witnesses sit in on meetings or communications during which managers ask about matters that could lead to the discipline of those workers.

While this right is important, it is also very limited. Often, practices at the workplace protect workers more broadly. Here’s what you need to know about broader workplace practices:

• Workers have a right to a witness during all communications about discipline. Weingarten does not give the worker a right to a witness if the company is only telling the worker what discipline the company is imposing. Under Weingarten, the worker is entitled to a witness only when the worker believes the company plans to ask about the matters the company may discipline the worker for.

• Workers automatically have the right to a witness. Weingarten gives the right to a witness only to those workers who request a witness and says that if a worker doesn’t request a witness, the worker gives up their right to a witness.

• Witnesses can ask questions. Weingarten does not give witnesses the right to ask questions.

• Witnesses can make the case for why the worker didn’t commit the misconduct or why the company shouldn’t impose the discipline it is considering. Weingarten does not give the witness the right to represent the worker or make arguments during the meeting.

• The company has to pay witnesses. Weingarten allows the company to question workers while the witness is not working.

In the original Weingarten case, a store chain refused several requests by a lunch counter worker for a steward to be present during two meetings with security. During the first meeting, security asked about four pieces of chicken the worker bought to contribute to a church.

After security verified that the worker did not steal the chicken, the worker burst into tears and said the only thing she ever got for free was her lunch. The store that the employee previously worked at provided free lunches to workers.

Because security believed that the policy at the new store was to charge workers for lunch, security questioned the worker about the free lunches, and again refused the worker’s requests for a steward. Security estimated that the worker owed about $160 for lunches they claimed the worker had stolen.

When the chain’s headquarters confirmed that the company never told the workers that they had to pay for lunch at the new store, security stopped questioning the worker.

The worker ignored the company’s request to not talk to anyone about the chicken or free lunches. The worker instead complained to the union. That union is now UFCW Local 455. The union filed an unfair labor practice charge with the NLRB.

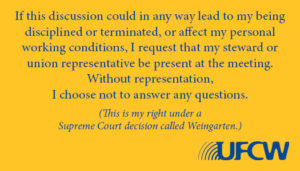

The NLRB ruled that workers who are represented by unions have the right to a witness, such as a steward or union representative, when the workers believe that the company may question them about something that may lead to their discipline. The worker – not the company – has the right to choose any steward or representative who is at the workplace. The Supreme Court upheld the NLRB’s ruling in the Weingarten decision.

At the beginning of the communication, the company must disclose the purpose and subject matter of the questioning and give the worker and the witness the opportunity to meet and talk. The role of the witness is to make sure the company questions the worker fairly and does not abuse the worker, and to listen and take notes.

If the company denies the request for a witness, the worker has the right to refuse to answer any questions and the company may not retaliate against the worker for doing so.

The case is NLRB v. J. Weingarten, 420 U.S. 251 (1975). Questions about Weingarten or how workers and local unions should try to change practices to give workers the broadest rights to witnesses can be directed to Assistant General Counsel Amanda Jaret in the International’s Legal Department at ajaret@ufcw.org.